1950s Dentistry or 21st Century Maths?

- Patrick Renouf

- Dec 10, 2024

- 3 min read

During a recent trip to the UK, I found myself doing what I often do—exploring the educational resources in bookshops. Being a curriculum nerd, I love seeing what’s new on the market and what’s being sold to parents as ‘support’ for their children.

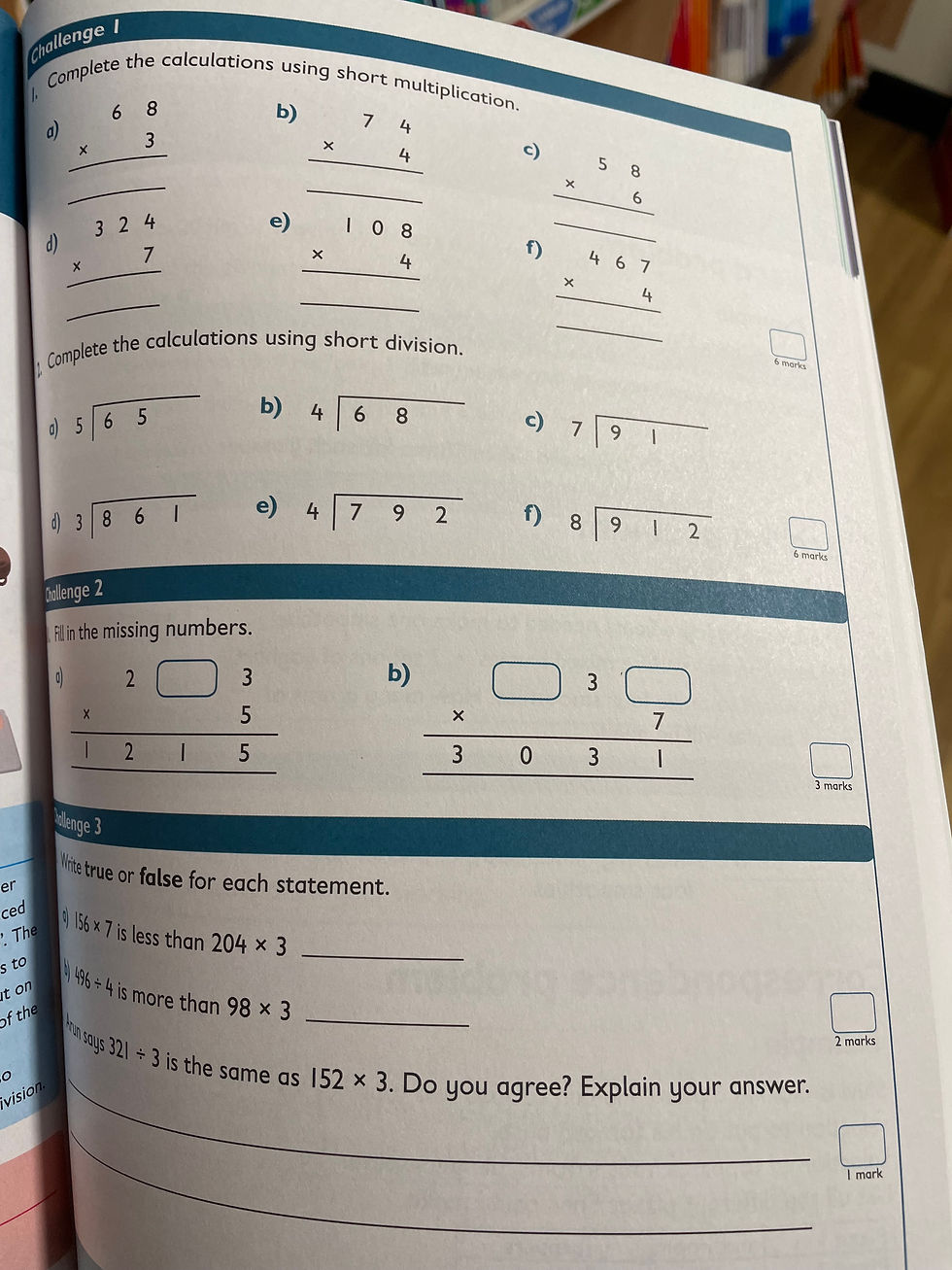

But as I browsed, my heart sank. What I saw in these books was the kind of thing I encountered when I started teaching in 1999. Despite all the research in recent years, education still seems alarmingly slow to change. The books on sale in the UK claiming to help children become better mathematicians appeared to be preparing them for a workforce based on 1950s values. Performative maths questions, algorithms, and a focus on speed dominated the pages—none of which truly builds the number sense needed to create confident, creative problem-solvers for 21st century challenges.

Imagine if dentistry were stuck in the 1950s. Would you take your child to a dentist still using outdated treatments and tools? I suspect not. We’ve embraced advancements in dentistry to reduce pain and improve outcomes—so why do we insist on a mathematical education that feels like pulling teeth?

Take the so-called 'Ten Minute Tests,' for example. They sound like friendly little quizzes, but for many children, they deliver maths anxiety in small, regular doses. These tests, aimed at Key Stage 1 children as young as 5-7 years old, send the harmful message that speed matters more than thoughtfulness.

Let me be clear: fluency is important. But testing isn’t the only—or the best—way to achieve it. You don’t fatten a pig by weighing it. What message does a child internalise when they struggle to complete these tests in ten minutes? Or when they fail entirely? For many, the takeaway is that maths is something to fear, something they’re not good at—and this belief can follow them for life.

It’s not just the children who are harmed. Parents, trusting these resources, might unknowingly reinforce damaging practices without realising there are better ways to help their child.

Instead of outdated drills and speed tests, we need to foster deeper number sense. Activities like Number Talks, hands-on problem-solving, and concept-based inquiry build the understanding and confidence our children need. These methods focus on thinking and exploring, showing children that maths isn’t about memorisation but about discovery and making connections.

We also need to shift the culture around maths. As educators, we must advocate for practices that promote curiosity and joy. As parents, we need to question the resources marketed as ‘helpful’ and seek alternatives that emphasise understanding over speed.

The stakes couldn’t be higher. The problems our children will face—climate change, technological advancement, global inequality—demand creative problem-solvers who think critically and approach challenges with confidence. Yet, our outdated approaches risk turning a generation away from maths before they even begin.

Imagine a world where children leave school not fearing maths but embracing it as a tool for understanding and shaping their world. A world where creativity, curiosity, and confidence define their relationship with numbers. That’s the future we should be striving for.

It’s time to stop settling for a 1950s approach to maths education and start embracing research-backed practices that truly empower young mathematicians.

Comments